Setiabudi Macet 1, originally uploaded by susiloadhy.Opponents of this policy argued this policy was only another strong evidence of the inability of the government of Jakarta to overcome traffic congestion. Students will be required to wake up early in the morning and they will be sleepy in class. The proposed policy will cause the tardiness of many students and many classrooms will be empty in the morning.

Given the limitation of the Jakarta city administration in overcoming traffic congestion, the policy to change school start time should be considered as a creative and innovative policy. The reaction to this controversial policy from the public should be anticipated by the city administration. The city administration Jakarta government must implement this policy consistently while still working to reduce traffic congestion through other policies.

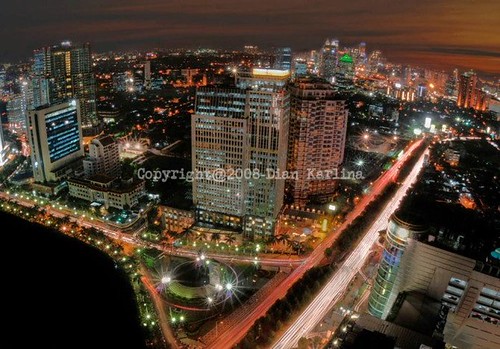

The traffic congestion in the capital, especially in the morning, will be slightly

reduced through this policy. The intensity of traffic jams in the capital in the peak hours will decrease because of the thirty minutes early trips of the studetns. The argument of the policy will reduce traffic congestion by 14 percent is reasonable. Data Pokok Kependidikan (Primary Data of Education) from the Jakarta's Office of Secondary Education shows that 1.75 million or 21 percent of the 8.3 million inhabitants living in Jakarta in 2006 are school aged people of 7-18 years old.

The traffic congestion in the capital can't be separated from the high rate of vehicle ownership by 9-11 percent per year that is not supported by the growth of road developent which is only less than 1 percent per year. The development of mass transportation system in the capital is still far from the expectation. The busway can reduce the intensity of traffic congestion in the main roads in the city center, but it has still yet to much untangle traffic congestions in other parts of the capital. In addition, the Mass Rapid Transit (MRT), which has long been planned, is stil unclear when to be realized.

Why you should use the Jakarta busway, originally uploaded by fishkid. The high rate of vehicle ownership and the high urbanization in the greater Jakarta area is also the results of the role of Jakarta as the capital of Jakarta and the country's economy and business center. Resolving the transportation problems in Jakarta must also consider developments occurring in the Jakarta's neighboring areas.

Given the various limitations in overcoming traffic congestion through the development of mass transportation system and the high rate of vehicle ownership motor vehicles that is difficult to be controlled, the plan to change school start time is an innovative and creative solution. It is better to implement this policy rather than waiting for the completion of the mass transportation system or the more road built in Jakarta.

In the early implementation of this policy, the city administration needs to tolerate the tardy arrivals of students to schools since the students and parents need some time for the adjustment to the early school hours. Similarly, the availability of public transportation in the early morning needs to be secured to provide services for the students.

In the next stage, the city administration needs to develop school buses that provide shuttle services for students. The provision of school buses will significantly reduce congestion because it will be reduce the number of private vehicles that were previously used to transport the students.

Other alternative that can be considered to reduce congestion school is to implement school attendance zone (rayonisasi). This policy will limit students in their choice of schools. The priority will be given to students who reside near the school. The implementation of this system will shorten the trip distance from the student residence to school, and will ultimately reduce traffic congestion.

In addition, the coordination of the school provision among the municipalities in the Greater Jakarta area needs to be strengthened. The availability of good schools in the Jakarta suburbs is very essential and it will prevent the residents in the suburbs of Jakarta from sending their children to better schools in the central city of Jakarta. The availability of good schools in the buffer areas of Jakarta will ultimately reduce the transportation problem in the capital.

(This article also appeared at The Jakarta Post on December 20, 2008)

Traffic and Change of School Start Time

Economic Crisis and Public Works Projects

city (11)1, originally uploaded by budibudz.

This year is an important year for policy makers for overcoming the global economic crisis that started from the financial crisis in the United States in the early 2008. The policy made in the beginning of 2009 will influence the future of the world's economy. In the United States, people have a high expectation on public works projects proposed by the Obama administration to overcome the economic crisis.

Barack Obama promised to build public works projects, the largest investment since the creation of the interstate highways fifty years ago. Public works projects are believed to revive the economy by creating new employments. In a meeting with Barack Obama in early December 2008, the US governors submitted the public works proposals that are ready to go in total amount of USD 136 billion including roads, bridges, etc. Those projects will create about 40,000 jobs for each USD 1 billion.

Lessons from the Great Depression

The current economic crisis is still less severe than the Great Depression in the 1930s, at least from the unemployment rate. In the 1930s, the unemployment rate reached nearly a third of the American workers. The current unemployment rate in the US at the end of December 2008 was 7.2% which was the highest record in the last 16 years, and this number is still very likely to increase. The current crisis has made economists and politicians think hard to avoid the second edition of the Great Depression.

In resolving the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the New Deal including the creation of jobs through public works projects in most parts of the US. One of the projects is Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) that built dam in the Tennessee rivers and several hydroelectric projects in the Tennessee region, one of the poorest region in the US. The history shows that the New Deal was able to address the Great Depression. In addition, TVA was able to create an energy source and 30,000 new jobs and also improve the quality of live of people in the Tennessee region.

An important principle of the programs developed by the FDR administration in addressing the Great Depression is the government intervention to the free market. This principle is an implementation of the advice of John Maynard Keynes, an interventionist government policy. The Keynesian economics will also be implemented by the Obama administration to resolve the current economic crisis.

Lessons for Indonesia

What can Indonesia learn from the global economic crisis? Learning from the success of the New Deal and the implementation of the Keynesian economics, it is clear that the government intervention is very vital to address the current economic crisis.

The budget of development that has been appropriated in the national budget (Anggaran Pendapatan dan Belanja Nasional) should be used for the real sectors, particularly in the regions of high unemployment rates. The public works projects, like TVA, such as dam and irrigation for extensifying agricultural lands outside the island of Java is quite relevant for the current situation in Indonesia. The extensification agricultural lands projects can also be directed to reduce the burden of Java island as the primary provider of the national food and alleviate poverty outside Java island.

If Indonesia wants to copy the green development initiatives as proposed by the Obama administration, Indonesia can develop a mass transportation system and alternative energy innovation projects. In the meantime, the conventional public works projects such as roads and bridges need to be focused on repairing the broken and bad infrastructures rather than developing new infrastructures.

(This post is an English version of the original article that appeared in the daily newspaper of Media Indonesia on January 15, 2009).

Jakarta Annual Flooding in February 2009

Fortunately, the extent of this year’s flooding was not as great as in the last two years. In February 2007, the worst flooding in Jakarta's history inundated about 70 percent of the city, killed at least 57 people and sent about 450,000 fleeing their homes. In February 2008, 37 of 267 subdistricts in Jakarta were inundated by more than 40 centimeters of water. Floodwaters caused public transportation, including the busway lines across Jakarta, to stop operations, leaving thousands of passengers stranded. Last year’s flood also inundated the Sedyatmo toll road to Soekarno-Hatta International Airport, which resulted in the cutting off the highway for a few days. Nearly 1,000 flights were delayed or diverted and 259 flights were canceled.

Interestingly, this year’s rainfall in Jakarta is higher than that in 2008 and is about the same with the 2007 rainfall. This year’s highest rainfall per day happened on February 2, 2009 reaching 339 millimeters. This year’s highest daily rainfall is slightly higher than that in 2007 (317 millimeters) and much higher than that in 2008 (117 millimeters). It is important to note that the high rainfall in the Jakarta’s neighboring areas was also blamed for the major flood in 2007.

In response to the last year's flood, Governor Fauzi Bowo set several strategic measures including ensuring the early warning systems are effective, dredging the river to enable the water flow properly, revitalizing the Pluit, Sunter and Riario dams, and placing mobile water pumps on the Sedyatmo toll roads to anticipate the blackouts. I would argue that the low enormity of this year’s flood is also subject to the effectiveness of such measures. Such measures may be able to mitigate the impact of this year’s flooding, but still cannot prevent the flooding.

Jakarta has 18 main canals and 500 smaller canals of 2 to 15 meters in width. The Jakarta’s network of canals performed only 50 to 70 percent of its capacity because these canals have been silted up with 9 million cubic meters of sediment and garbage (The Jakarta Post, February 2, 2009). Furthermore, Budi Widiantoro of the Jakarta Public Works Agency blamed the garbage as the main cause of the low capacity of Jakarta’s canals (The Jakarta Post, January 14, 2009). This is certainly a big challenge for the Jakarta administration to educate its residents to not throw away garbage into canals. Dredging canals will not be an effective way of reducing flood if people still throw away garbage into canals.

In the aftermath of the 2002 major flood, the central government and Jakarta administration plan to build the East Flood Canal project. The project is aimed at reducing floods in a 270-square-kilometer flood-prone area of East and North Jakarta, but it has progressed very slowly. As of February 2009, the Jakarta administration has procured only 62 percent of the needed land. The East Flood Canal is sought to be most feasible solution for preventing future flooding in Jakarta, but apparently the East Flood Canal is not easy to be materialized.

Neither dredging the canals and rivers nor building new canals is a sustainable solution for preventing future flooding in Jakarta. As the economic, commercial, cultural and transportation hub of the nation, Jakarta is poised to grow faster than other parts of Indonesia. The annual floods are strong evidence that Jakarta cannot sustainably accommodate its rapid growth. Indonesia needs to redistribute the central functions from Jakarta to other parts of the nation and create more urban agglomerations to pull urban growth away from Jakarta. Relocating central functions out of Jakarta will reduce the rapid growth in Jakarta and eventually become a sustainable solution for preventing future flooding in Jakarta.

(This article also appeared at The Jakarta Post on February 28, 2009)

The Collapse of Situ Gintung Dam and Poor Enforcement of Spatial Plans

Situ Gintung Tragedy -another-, originally uploaded by aris-ressy.

The heavy rain in the area of Situ Gintung was often blamed by many people as the culprit of the disaster. The heavy rain is only a trigger but is not a cause of the dam collapse. Heavy rains were often recorded in the Situ Gintung area, as happened in 2007 that caused big floods in Jakarta, but they did not break the Situ Gintung dam.

I would argue that the collapse of the Situ Gintung dam was caused by the low enforcement of the spatial planning laws in Indonesia. Indonesia has had spatial planning laws since 1992 through the enactment of the spatial planning law 24/1992. This spatial planning law differentiated spatial plans by two main functions including conservation areas (kawasan lindung) and cultivation areas (kawasan budidaya). Conservation areas include areas surrounding springs and lakes such as the Situ Gintung area. The spatial planning law 24/1992 clearly stipulated that the conservation areas have the main function for protecting the environmentally sensitive areas such as areas surrounding springs or lakes. Activities that are allowed in the conservation areas are very limited including conservational and rehabilitation activities, research and environmental tourism.

Referring to the spatial planning law 24/1992 or the current spatial planning law 26/2007, the Situ Gintung area was supposed to be a conservation area. Assigning the Situ Gintung area as a conservation area means only activities protecting the environmentally sensitive area of Situ Gintung will be allowed in the area. Residential areas will not certainly be allowed in the conservation areas including in the Situ Gintung area.

The disaster of Situ Gintung is the impact or negative externalities of the activities in the area that cannot protect and conserve the environmentally sensitive area of Situ Gintung. More than 40 percent of the 112.5 hectare water catchment area of the Situ Gintung was identified as residential areas (Kompas April 1, 2009). Such a large proportion of residential areas in an environmentally sensitive area are clearly an indication of the low enforcement of spatial planning laws. It is very likely that the residential areas would expand in the Situ Gintung area in response to the population growth if the disaster did not happen.

The current spatial planning law 26/2007, adding several clauses from the spatial planning law 24/1992 such as imposing administration and criminal sanctions for those who violate the laws, is poorly enforced. The new stipulations in the spatial planning law 26/2007 including disincentive and incentive in the spatial plan implementation have not been fully enforced. The violation of spatial plan law in the Situ Gintung area is only one of many violation cases in Indonesia. The Indonesian Planning Association also acknowledged the spatial plan law violations in other Indonesian cities in their press release in the aftermath of the disaster of Situ Gintung. The enforcement of the spatial planning law will be a difficult task without the understanding of residents about the importance and essence of spatial plans.

Situ Gintung Tragedy, originally uploaded by aris-ressy.

Indonesian people need some more time and efforts to “learn” the importance of spatial plan for the sustainable development in Indonesia. The disaster of Situ Gintung should be interpreted as a learning process for Indonesian people about the consequences of the spatial planning law violation. Indonesia needs to learn from the mistakes in the Situ Gintung case for preventing similar cases in the future. Indonesian people need to understand the importance of spatial plans for their public health, safety and welfare. Such an understanding is quite important for the Indonesian governments to enforce the spatial planning law 26/2007 in order to create safe, convenience, productive and sustainable places in Indonesia.

Envisioning City without Cars

Setiabudi Macet 1, originally uploaded by susiloadhy.When a new highway was built or a road was widened, it will only solve the traffic congestion for a short period of time. After a few years, the new highway will fill with traffic that would not have existed if the highway had not been built. Similarly, the widened road fills with more traffic in a few months. Such phenomenon is called induced demand. Because of the induced demand, neither building new roads nor widening roads are the long-lasting solution to traffic congestion.

There are several possible solutions to eradicate traffic congestion problems and one of them is the reduction of private vehicle uses. I read an article in the New York Times (May 12, 2009) on a suburb town without cars in Germany with great interest. Streets in this upscale town are completely car-free except the main thoroughfare and a few streets on on edge of the town. The residents of this town are still allowed to own cars, but parking is relegated to two large garages at the edge of the development.

The Vauban town, is located on the outskirt of Freiburg, near the French and Swiss borders and home to 5,500 residents. The residents are heavily dependent on the tram to downtown Freiburg and many of them take to car-sharing when longer excursions are needed. Seventy percent of Vauban's families have no cars. They do a lot of walking and biking to shops, banks, restaurants, schools and other destinations that are interspersed among homes. The town is long and relatively narrow and provides an easy walking access to the tram for every home.

Creating places with more compact design, more accessible to public transportation and less driving is the envision of urban planners in the 21st century. The Vauban town is an exemplar of the 21st century urban design in response to the threats of greenhouse gas emission and global warming and the dwindling oil supply.

I could argue that the Vauban's urban design is the extention of the New Urbanism. The New Urbanism is a school of urban design arose in the U.S. in the early 1980s. This school of urban design promotes several key principles including walkability and connectivity, mixed land uses, and high density. There have been many the New Urbanist towns in several countries, but cars still fill the streets of these towns.

The Vauban town provides an example of the possibility of creating city without cars. The walkable and mixed-land-uses urban design, easy access to public transportation and excellent public transportation system as demonstrated in the Vauban town are the components for creating city without cars.

Cars are still a luxury item for many Indonesian families. Many urban residents, particularly those live in kampung kota, do not own cars and are used to living without cars. Streets (gang) in Indonesia's kampung kota are too narrow for cars and the residents are used to walking and biking to their destinations. Kampung kotas are located in the center of urban areas and relatively accessible to public transportations. In reference to the New Urbanism concept, the Indonesia's kampung kota has implemented the principles of walkability and high density.

Indonesian planners need to appreciate the existence of kampung kota in terms of lacking driving needs. Kampung kota residents will be less likely to have a demand for cars when their neighborhoods are accessible to public transportations and the streets in their neighborhoods remain narrow. Kampung kota residents need to remain lack of driving needs for reducing the car ownership rate in urban areas.

For new developments in suburb areas, Indonesian planners can emulate the success of the Vauban town. Driving needs are profoundly affected by the urban design and the high access to public transportation. It makes sense to envision and is not all impossible to create a city without cars.

(This article also appeared at The Jakarta Post on June 2, 2009)

This blog in the GPEIG Newsletter

amazing, originally uploaded by BESTPHOTO.

GPEIG stands for Global Planning Educators Interest Group and is an interest group under the ACSP (Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning). The mission of GPEIG is to foster global perspective in planning education and research. This link provides more information about GPEIG.

Following is the story about this blog in the GPEIG newsletter that can also be found in this link.

I am honored to share my blog of Indonesia’s Urban Studies with the readers of

the GPEIG newsletter. The blog, located at http://indonesiaurbanstudies.blogspot.com/ was created in January 2007. As mentioned in the first post of my blog, the purpose of this blog is to contribute to the advancement of urban studies and planning in Indonesia, and was inspired by the success of Randall Crane’s blog of Urban Planning Research.

My blog includes a wide-ranging collection of reflections and essays about urban issues in Indonesia, including poverty, informal sector, transportation, land uses, spatial planning, urban primacy and global warming. My reflections are primarily focused on the current urban issues in Jakarta and are based on my regular reading of two Indonesian newspapers, Kompas and The Jakarta Post. Most news stories in both newspapers are about Jakarta, and a few stories are about other cities in Indonesia. That’s why my blog posts are mainly about Jakarta.

Several urban issues in Jakarta are discussed in my blog, including the banning of

motorcyclists from Jakarta’s main roads, extortion by thugs of street vendors, an upscale neighborhood’s resistance against a new busway corridor plan, the Jakarta City Council’s rejection of a plan of converting gas stations into green areas and the change of the school start time. The blog also includes the reflections of the last three years of annual floods that inundated Jakarta. Interestingly, the floods always occurred in the first week of February. The blog documents the impacts of the flood each year and government efforts at preventing the floods. These posts were also submitted to and run by The Jakarta Post in its Op-Ed sections.The blog also presents a number of essays including the history of urbanization and

suburbanization in Jakarta, the dominance of Jakarta in Indonesia’s economy,

urban planning and the informal sectors in developing countries, challenges of the planning profession in Indonesia, and a book review of Christopher Silver’s Planning the Megacity: Jakarta in the Twentieth Century.

Nearly 50,000 visitors have come to my blog and most of them are via Google. Many visitors also came from other websites and blogs that have a link to my blog, including the ACSP’s website. A number of students from many parts of the world contact me after visiting my blog for a variety of reasons, including asking further questions or for detailed data, asking for data sources in Indonesia, asking for definitions of urban terms, asking me to review their work on Indonesia, or simply for appreciating my work. In addition to students, a journalist of Singapore’s The Straits Times and a Norwegian journalist contacted me for their stories of Jakarta. I was also invited by the editors of an Australian magazine and several Indonesian newsletters to submit stories about urban issues in Indonesia. All these invitations and interviews came to me through visits to my blog.

Furthermore, I can trace from where and how long the visitors visit my blog. They come from countries all over the world, including countries in Africa and South America. I am amazed by their interest in Indonesia’s urban issues, and hope that my blog contributes to their interests.

When I started nearly three years ago, I never expected to get what I have accomplished with my blog today. We can witness the power of the Web in building and shaping our society. The world is now directed by the citizens of the new digital democracy. Blogging is a good way for scholars to be a part of this new world of digital democracy. I have learned from my blog that the voice of scholars in the blogosphere is well-respected and appreciated. The blog audiences have a lot of choices to read and they find the voice of scholars worth reading.

A city without social justice: Jakarta needs more green space, but not the expense of the poor

http://insideindonesia.org/content/view/1246/47/

In case of the link is not available, I copied the article as you can find below. Thank you.

A city without social justice: Jakarta needs more green space, but not the expense of the poor

Jakarta is not only Indonesia’s capital and most dynamic city, it is also beset with a plethora of 21st century urban problems. As its population grows, its green spaces shrink. In the first half of the twentieth century Batavia, colonial capital of the Netherlands East Indies, was a small urban area with approximately 150,000 residents. Batavia has become Jakarta, Indonesia’s megacity of 14 million.

Green spaces in the city have shrunk along with this leap in population. As recently as 1965, green areas made up more than 35 per cent of Jakarta’s land area. Currently, they account for only 9.3 per cent, far below the target of 30 per cent set by Law No 26 of 2007 on Spatial Planning.

Shrinking green areas

As Jakarta is certain to continue to grow, the city’s master plan to protect remaining green spaces and add some more, especially along riversides, offer some hope. The city’s current 2000-2010 master plan aims to achieve green areas (legally defined as areas where plants can grow) of 13.94 per cent of the total city area. This is an excellent goal, but it is modest when we compare it to similar plans in the past. The 1965-1985 master plan, for example, planned for green areas covering 27.6 per cent of Jakarta’s land area. In part, these plans are simply catching up with reality. New luxury homes, condominiums, shopping malls, hotels, commercial buildings and offices have proliferated in Jakarta over the last three decades. Many have been built at the expense of green areas and have paved over water catchment areas, making the city more prone to floods.

Annual floods in Jakarta point to an urgent need to protect existing green

areas in the capital – and to create new ones.

Not surprisingly, annual floods are becoming more severe, and more deadly. The worst flood in memory occurred in February 2007, inundating about 70 per cent of the city. It killed at least 57 people and sent some 450,000 fleeing their homes. In the aftermath of the flood, Environment Minister Rachmat Witoelar put the blame on excessive construction of residential and commercial buildings, which now cover many of the city’s former green areas.

Annual floods in Jakarta point to an urgent need to protect existing green areas in the capital – and to create new ones. Green areas absorb rainwater and thus help prevent flooding. Green areas also help make cities more sustainable and livable.

Canal - Jakarta, originally uploaded by pyjama.

As part of its master plan, Jakarta’s administration has planned to expand the city’s green areas to nearly 14 percent of the city’s area by next year. However, even this modest expansion will come at the expense of some of Jakarta’s most powerless residents. Often, when the city government creates new green spaces it does so by evicting the city’s poor residents and operators of informal sector businesses.

For example, the restoration of Ayodia Park (on Jalan Barito in South Jakarta) led to evictions of fish and flower traders in January 2008. Many of the traders had run their businesses in that area for more than 20 years, yet Jakarta Governor Fauzi Bowo argued that the vendors were there illegally and had no right to the land. In February 2008, the city administration evicted ceramics sellers from beneath a highway overpass in Rawasari, Central Jakarta, in order to expand green spaces. It did the same to about 1400 families who had lived for years in Kampung Bayam (North Jakarta) in August 2008. In this case the aim was to restore the 66 hectare BMW Park (BMW in this case stands for Bersih, Manusiawi, dan Wibawa – Clean, Humane, and Esteemed). The Kampung Bayam eviction turned into a melee as many squatters, mostly women and children, resisted officers’ efforts to remove them.

While Jakarta authorities often use force to ‘free’ land used by the city’s poor, they lack the courage to prevent construction of the condominiums, malls, hotels and commercial or offices that developers and the rich build in designated green areas in blatant violation of the city’s spatial plans. The Indonesian Forum for the Environment (WALHI) counted numerous Jakarta developments that converted green areas into malls and other commercial buildings, in violation of Jakarta’s spatial plan. WALHI’s May 2009 report identified these illegal developments in Kelapa Gading, Pantai Kapuk, Sunter, Senayan, and Tomang. Governor Fauzi Bowo told the media in February 2008 that it would not be realistic to demolish such buildings to restore green spaces.

The authorities often use force to ‘free’ land used by the city’s poor, but they

lack the courage to prevent construction of condominiums, malls, hotels,

commercial buildings and offices

Jakarta now has about 60 mid-size and large shopping malls. According to the Urban Poor Consortium (http://www.urbanpoor.or.id/ ), a Jakarta advocacy organisation, only about 500,000 Jakarta residents can afford to shop in those malls. The malls do not serve Jakarta’s poor, who outnumber Jakarta’s mall-shopping rich by seven-to-one.

Social injustice

Not only has the Jakarta government failed to prevent the loss of existing green spaces to malls and commercial buildings, influential commercial interests have also scuttled plans to re-establish green spaces. For example, in March 2008, Jakarta’s City Council rejected the Jakarta Parks Agency’s plan to create green spaces in place of 29 gas stations, caving in to the demands of the politically powerful gas station owners.

The city administration deserves support for planning to create additional green spaces.But it should not do so by mistreating poor people and the informal sector. It seems that Jakarta politicians find it easier to expand green areas by demolishing poor residents’ homes and forcing informal sector workers off public space, than by preventing, stopping, or demolishing developments that benefit only the wealthy.

Deden Rukmana (rukmanad@savannahstate.edu) is assistant professor and coordinator of the graduate program in Urban Studies and Planning at Savannah State University, USA. He publishes Indonesia’s Urban Studies (http://indonesiaurbanstudies.blogspot.com/ )

Restoring Green Areas in Jakarta

On November 8, 2009 Jakarta’s Governor Fauzi Bowo closed and locked a gas station located on Jl. Jendral Sudirman to symbolically close down 27 gas stations and convert the areas into green spaces. The Jakarta Parks and Cemetery Agency announced that the 27 gas stations will be closed by the end of the year and the closure of these gas stations will add another 10,505 square meters of green areas in Jakarta (The Jakarta Post, November 11, 2009).

The conversion of gas stations into green areas is to meet the target for green areas in Jakarta stipulated in the Jakarta spatial plan 2000-2010 to cover 13.94 percent of Jakarta's total 63,744 hectares by 2010. In 1965, green areas made up more than 35 percent of Jakarta and have been shrinking ever since. Currently, green areas in Jakarta account for only 9.3 percent of the city's area, far below the target of 30 percent set by the Spatial Planning Law 26/2007.

I commend Governor Fauzi Bowo and his city administration for converting gas stations into green areas because of two main reasons. First, the conversion of gas stations into green areas is a good precedent for implementing spatial plans. Over the years, the spatial plan seems to be a legal document that is not fully enforced and implemented. The 27 gas stations are located in the areas designated as green areas in the Jakarta spatial plans 1965-1985, 1985-2005 and 2000-2010. For many years, the city conceded to the powerful owners of the gas stations and could not enforce and implement the spatial plans. In March 2008, the city proposed the plan of the gas stations conversion but it was rejected by the Jakarta City Council. This year, the city resubmitted the proposal and it was approved by the newly elected Jakarta City Council.

Second, we must put a stop to disappearing green areas in Jakarta. Green areas are an important urban element that can help make cities self-sustainable and more livable. Annual floods in Jakarta indicate an urgency for green areas in the capital, because they absorb rainwater and help to avert flooding. New homes, condominiums, malls, hotels and commercial and office buildings have proliferated in Jakarta over the last three decades. These new developments have come at the cost of green areas and have decreased water catchment areas, making the city more prone to floods. Not only will the conversion of gas stations into green areas add the green areas but also contribute in preventing annual floods in Jakarta.

The cost of closing down and converting each gas station was around Rp. 75 million and I would argue that the benefit of the conversion of gas station into green areas will be much more than Rp. 75 million over the years. In addition to reducing the risk of floods, the new green areas will beautify and make Jakarta more livable. I would also suggest that the green areas that are close to residential areas be designed as recreation parks. The recreation parks will serve as a mode to build healthy, strong and vibrant neighborhoods and it will benefit the city even more. The conversion of these gas stations into green areas will also restrain the increasing city's carbon dioxide levels. The green areas can serve act as sponges for such pollutants.

In sum, the decision of the Jakarta’s administration to close down the gas stations and convert them into green areas in order to comply with the Jakarta spatial plan is a good move and should be appreciated. Not only will this decision become a good precedent for implementing the spatial plans in Jakarta or even in other areas in Indonesia, but also will provide a lot of benefits for the city and its residents.

(This article also appeared at The Jakarta Post on December 12, 2009; was reposted at Creative Cities ; was cited at Treehugger and at Reflection on Auckland Planning )

Climate Change and Urban Development

Welcome-to-the-Greenhouse, originally uploaded by mix's.

This post is an English version of my article published in the Indonesian newspaper of Kompas on Tuesday, December 15, 2009.

The attention to climate change and global warming is now on the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, Denmark on December 7-18, 2009. This conference is expected to reach a new agreement on decreasing global emissions of greenhouse gases after the ending of the Kyoto Protocol in 2012.

As one of the tropical countries with large forest areas, Indonesia is expected to play an important role in absorbing the emissions of carbon dioxide that cause the increase of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Transtoto Handadhari (Kompas, December 7, 2009) reported that Indonesian forests have the carbon dioxide absorption as many as 25,733 billion tons excluding peat forests and dry lands. The government of Indonesia set a target of reducing the carbon emissions by 26 percent in 2020 through many ways including the expansion of new forests as much as a half hectare per year, the expansion of community forests about 4 million hectares, and the decrease of hot spots about 20 percent.

The decrease of carbon dioxide emissions for addressing the global warming is not only the responsility of those who work in forests, but also that of all citizens. Urban residents play also an important role in decreasing the carbon dioxide emissions. Human activities that use fossil fuel are a big contributor in the global warming. Increasing the efficiency of electricity uses such as lighting, cooling or the uses of electronic tools and recycling are some ways that can be offered to address the global warming.

Copenhagen UN Climate Change Conference, originally uploaded by United Nations Photo.

Urban Green Areas

Urban development can be also aimed at addressing the global warming. Urban green areas are often sacrificed in urban developments in order to keep up with the fast-growth of urban population. Jakarta, for instance, in 1965 had green areas as much as 30% of the total Jakarta areas, and the proportion of green areas has been decreasing to 9.3% in 2009. The decrease of green areas also occurs in most Indonesian cities. Green areas are an important component of urban development, not only to create a city more beautiful and greener, but also to absorb carbon dioxide from human activities particularly transportation.

Green areas can also play a role of mitigating the impact of climate change such as floods and the rise of sea level. Green areas can be water catchment areas for preventing floods. In metropolitan areas, such as Jakarta, the area vulnerability to global warming will be even higher due to the land subsidence that is caused by extensive underground water exploitation.

The expansion of green areas should be one of the urban development priorities in in Indonesia. The ideal of green areas in urban areas is 30% of the total urban area as stipulated in the Spatial Planning Law 26/2007. This number is not easy, but is not impossible to achieve either. Lately, the Jakarta administration closed 27 gas stations located in green areas and converted them into green areas. Such a decision demonstrates a strong commitment from the Jakarta administration to expand green areas and can be followed by other cities in Indonesia or even in the world.

Mass Transit and Urban Sprawl

Urban development in metropolitan areas such as Jakarta needs to develop mass transit such as subway and monorail. The current public transportations such as busway and other public transportations need to expand the services and integrate with the needs and affordability of residents. Converting private vehicles to mass transits or other public transportation will reduce the use of fossil fuel. The decrease of fuel usage per capita in transportation will significantly reduce the carbon emission.

Planet Jakarta, originally uploaded by diankarl **will visit you soon**.

The flawed planning process of the 2030 Jakarta spatial plan

The objections to the 2030 Jakarta spatial plan from several organizations in Jakarta are the answer of the above question. The 2030 Jakarta spatial plan is not a valid plan yet. WALHI (The Indonesian Forum for Environment) and 28 other NGOs in Jakarta opposed the 2030 Jakarta spatial plan and will offer an alternative plan to be submitted to the City Council. They formed an alliance called Jaringan Masyarakat Sipil untuk Tata Ruang Jakarta 2030 (the network of civil society for the 2030 Jakarta spatial plan) and argued that the Jakarta 2030 spatial plan pays less attention to the poor people and the environmental sustainability. The Citizens Coalition for Jakarta 2030, an organization formed in December 2009 by several concerned Jakarta residents, also raised objections to the planning process of the 2030 Jakarta spatial plan including the lack of citizen participation. The coalition has held several public discussions, launched a website and a group in Facebook and conducted public opinion surveys to aggressively seek input from residents.

The objections to the 2030 Jakarta spatial plan illustrate that the planning practice in the 21st century is facing greater challenges than that in the 20th century. Ten years ago or even 25 years ago, there were very few objections to the spatial plans from the residents when the Jakarta administration prepared the 2005-2010 and the 1985-2005 Jakarta spatial plans. The planning practice in the 21st century is dealing with pluralism and communities characterized by fragmented power and distrust of government and experts.

Local communities have experimental, grounded, contextual, intuitive knowledge, which are manifested through speech, songs, stories, and various visual forms rather than the more familiar kinds of planning sources such as census data, and simulation model. Planners in the 21st century have to learn to access these other ways of knowing.

The planning practice in the 21st century calls for community-based planning. It would replace the reliance on state-directed futures and top-down processes. Citizen participation can lead to better public policy. Through such selfish participation, the government is informed of these interests and pressured to respond. In this way, it produces public goods more closely attuned to citizen needs than it would if there were no participation.

In many American cities, a comprehensive plan is prepared in more than 3 years. There is a visioning, a process by which a community defines the future it wants through an extensive public involvement. Many communities develop a vision at the beginning of the planning process and the citizen input becomes meaningful. Stakeholders should have faith in the value of public dialogue. The extensive public involvement can include broad-based advisory committees, community-wide public opinion survey, town hall meetings, information in mass media including TV, radio, and newspaper, community leadership training, public hearing, and information through the internet. Visioning can add to the cost of the planning process, but it can serve as a catalyst that can bring city residents together to discuss about their future in new ways.

(This article also appeared at The Jakarta Post on February 6, 2010; was reposted at Koalisi Warga untuk Jakarta 2030)

Jakarta Annual Flooding in February 2010

I have written on the floods in Jakarta every year since 2007 when the worst flood in memory inundated about 70 percent of the city, killed at least 57 people and sent about 450,000 fleeing their houses. In 2008, the floods inundated 37 out of 267 sub-districts in Jakarta by more than 40 centimeters of water. The Sedyatmo toll road to Soekarno-Hatta International Airport was inundated and nearly 1,000 flights were delayed or diverted and 259 flights were cancelled.

Motorists fought against flood, originally uploaded by Deden Rukmana.

Interestingly, this year’s floods in Jakarta inundated more areas than last year’s floods despite a lower level of rainfall. This year’s flood also killed at least 2 people and displaced more than 1,700 in Kampung Melayu, Bukit Duri and Bidaracina areas from overflowing Ciliwung river (The Jakarta Post, February 13, 2010 and February 20, 2010).

In the aftermath of the annual floods in Jakarta, which always occurred in the month of February, the government has been always focusing on releasing floodwater as fast as possible into the sea, particularly on the development of the East Flood Canal. The project was launched in the aftermath of the major floods in 2002 and has progressed very slowly due to the complicated process of land acquisitions. The project finally reached the sea on December 31, 2009, but there are still unfinished works in several spots. In the aftermath of this year’s flood, the government planned to connect Ciliwung River to Cipinang River which is now attached to the East Flood Canal.

The East Flood Canal has been considered as the most feasible solution for preventing future floods in Jakarta, but it clearly cannot prevent the flooding entirely. The East Flood Canal, along with dredging the rivers to enable water to flow properly, is only able to mitigate the impact of the flooding. We have also witnessed an effective flood warning system in this year’s floods in mitigating the impact of the floods.

Road of flood, originally uploaded by Deden Rukmana.

Jakarta needs bold moves for preventing future flooding. Rapid urbanization in Jakarta must be reduced. A possible way of reducing urbanization in Jakarta is to redistribute the central functions of Jakarta to other parts of the nation and strengthen other urban agglomerations in Indonesia to pull urban growth away from Jakarta. The idea of Indonesian capital relocation out of Jakarta needs to be strongly reconsidered.

Water catchment areas, green areas and wetlands that have been converted into urbanized areas need to be re-functionalized as non-urbanized areas. An exemplary model of this reconversion is a decision of the Jakarta administration to convert 27 gas stations in five districts in Jakarta into green areas in November 2009. The closure of these gas stations will add another 10,505 square meters of green areas in Jakarta. This is a bold move of the Jakarta administration in expanding the green areas in Jakarta. Such a move needs to be replicated and expanded to other areas in Jakarta. Currently, green areas in Jakarta account for less than 10 percent of the city’s area, far below the target of 30 percent set by the Spatial Planning Law 26/2007.

The 2030 Jakarta spatial plan, an important and comprehensive document for shaping the next 20 years of Jakarta, is now in the making. The bold move of expanding the green areas in Jakarta needs to be strongly considered in the 2030 Jakarta spatial plan. The cost of converting urbanized areas into green areas will be expensive, but such a sacrifice is needed for the future of Jakarta, including preventing future floods.

(This article also appeared at The Jakarta Post on March 20, 2010)

Citarum floods and urban planning

Sungai Citarum Indonesia dianugerahkan Sungai Terbersih Di Dunia, originally uploaded by omaQ.org & Red Frame Memories.

In the long run, the propasals from the Governor of West Java will not sustainable if they are not supported by sustainable urban planning that considers the ecological and environmental balance in the broader context. The conversion of water catchment areas and forests into agricultural areas is also a result of unsustainable urban planning.

The Citarum river basin has an area of 718,268 hectares and covers eight cities and districts in the West Java Province including Bandung City, Bandung Regency, Cimahi City, Sumedang Regency, Cianjur Regency, Purwakarta Regency, Karawang Regency, and Bogor Regency. The eight cities and regencies are an area that experienced a high level of urbanization. High level of urbanization in the urban areas in the Citarum river basin is one of the factors that need to be strongly considered for preventing the occurence of Citarum flood in the future.

Anakku, originally uploaded by enhaka92.

Bandung City, Bandung Regency, Sumedang Regency and Cimahi City are included in the Bandung Metropolitan area which has a high level of urbanization. Meanwhile, the Regencies of Bogor, Cianjur, Karawang, and Purwakarta are the suburbs of Jakarta that have a high level of the conversion agricultural lands to urban areas. The high level of urbanization in Jakarta and Bandung Metropolitan megapolitan has resulted in the increased demand for urban land for accommodating population growth and the development of urban sectors such as industry and services.

Without strict restrictions on the expansion of urban areas, the conversion of agricultural land into residential areas or industrial areas in the suburbs will continue to happen. The conversion of agricultural land in the suburbs will also have an impact on conversions that occur in water catchment areas and forests. Farmers who previously worked on his land on the outskirts of the city will look for his new farm to water catchment areas and forests. Such a process of land succession will continue in line with the urbanization rate, except where restrictions on the expansion of urban areas is applied.

Many states in the United States have imposed restrictions on urban areas so as not to expand to agricultural areas or other environmentally sensitive areas. Policies such as growth management or urban containment has been proven to limit the growth of urban areas and protect agricultural and forest areas. Although this policy in the short term will impact negatively on the provision of affordable housing but in the long term this policy will be more sustainable.

The pressures due to the high urbanization rate in urban areas in the Citarum river basin should be limited and should not interfere with the preservation of the upstream area of Citarum river basin. The development of urban areas in the Citarum river basin should be restricted and not allowed to convert agricultural land to urban areas. The preservation of agricultural land in the suburbs will indirectly reduce pressure on the forest conversion in the upstream area of Citarum river basin. In the long term, it will result in the environmental sustainability in the Citarum watershed and will prevent the floods from happening in the future.

Urban Planning and Local Wisdom: The Shift toward Postmodernism and a New Urban Theory from Third World Cities

Abstract

Local wisdom is often held as the best solution to the challenges of urban planning that are increasingly getting more complex and obscure. The planning practice in the 21st century is facing greater challenges than that in the 20th century. Some of the challenges are the complexity of the problems and the elusiveness of solutions to those problems. This article discusses the importance of local wisdom in urban planning within the context of the shift from modernism to postmodernism and the emergence of a new urban theory rooted from cities in the developing countries including Indonesian cities.

Introduction

For decades, the practice of urban planning has been concerned with making public or political decisions more rational. Means-ends rationality was considered as a useful and effective concept in the planning practice. Most leading planning scholars (Altschuler, 1965; Blowers, 1986; Friedmann, 1987) agreed that planning is associated with rationality. Rational planning as a practice of modernist planning was perceived as efficient planning accommodating a process in which course of action selected rationally to maximize the attainment of the relevant ends. Rational process of selecting the best means to achieve some pre-determined ends based on assessment of the consequences of alternative solutions.

On the contrary, post modernists challenge the knowledge foundation of modernist planning practice and theory. They posit that the postmodern era characterized by fragmented power, distrust of government and experts, and incommensurable discourse are not suitable for the practice of modernist planning. Modernist planning that identifies a relation between means and ends in society needs to be justified in terms that are broader than mere self-interest. There is a need of greater and more explicit reliance on local wisdom and more people-centered.

The practice of urban planning in the developing countries including Indonesia has been dominated by two urban theories, the Chicago School of Urban Sociology and the Los Angeles School of Urban Geography. Both urban theories are rooted in the developed world. Planning practices are constantly borrowed and replicated across borders (Roy 2005). Planning practices that replicate both urban theories through the dichotomy of developed and developing countries become ubiquitous. This becomes a problem when such a replication is no longer relevant with the unique urban phenomenon in developing countries including in Indonesia.

The purpose of this article is to identify the importance of local wisdom which has often been held as the best solution to the challenges of urban planning within the context of the shift from modernism to postmodernism and the emergence of a new urban theory rooted from cities in the developing countries. Based on the importance of local wisdom, this paper concludes with suggestions of modification to urban planning practice.

Modernist Urban Planning

Urban planning can be defined as a systematic attempt and actions in the public domain to shape the future of urban areas. There are many ways for urban planners to shape the urban future as follows:

- formulate policies to meet the needs of communities including social, economic, and physical needs and they develop the strategies to make these plans work

- develop plans for land use patterns, housing needs, parks and recreation facilities, transportation systems, economic development, environmental protection and other aspects of the future

- work with the public to develop a vision of the future and to build on that vision

function as mediator among conflicting community interests; they may also become facilitators using their professional judgment to help identify the best resolutions to the conflict - advise public officials and citizens in shaping the future design and manage the planning process and attract public to involve in the process.

A practice of modernist planning is the positivistic rational comprehensive planning model (Innes, 1997; Harper and Stein, 1995). This planning model was developed systematically to find the best process in which course of action selected rationally to maximize the attainment of the relevant ends. This planning model attempts to formulate rational process of selecting the best means to achieve some pre-determined ends, a way of choosing the correct answer based on assessment of the consequences of alternative solutions.

The stages in rational planning including formulation of goals and objectives, identification and design of major alternatives for searching the goals, prediction of major sets of consequences that would be expected to follow upon adoption of each alternative, evaluation of consequences in relation to desired objectives and other important values, decision based on information provided in the preceding steps, implementation of this decision through appropriate institution, and feedback of actual program result and their assessment in light of the new decision situation have employed scientific method. Numerous scientific methods have been formulated to develop the stages in rational planning. Development of methods for each rational planning process was conducted by applying two methods of reasoning of deductive and inductive approaches.

Rationality has been extensively explored by many scholars such as Banfield, Friedmann, Mannheim, Weber, Simmie, and Faludi. Rationality is accepted in planning, since there is nothing wrong with rationality decisions after they have been formulated as long as the attempt is successful. Rational planning results in growth as a product, and the rational planning process may be viewed as a vehicle for the very process of growth. When the rational planning was used as primary planning paradigm, planning education was a matter of technical training, the focus was on the empirical and the quantitative (Harper and Stein, 1995).

Beauregard (1991), in his article entitled Without a Net: Modernist Planning and the Postmodern Abyss identifies the characteristics of modernist planning. He posits that (1) reality can be controlled and perfected, (2) the world is malleable because its internal logic can be discovered and manipulated, (3) planning is part of the struggle to make ourselves at home in a changing world., (4) planners involvement was as contributors to utilitarian understanding and not as people of action, (5) planners could claim a scientific and objective logic, (6) comprehensive solutions have a unitary logic, and (7) synthetic city allows planners to claim a privileged position in the realm of specialist.

Sandercock (1998) in her seminal book on post-modernism entitled Toward Cosmopolis: Planning for Multicultural Cities summarizes the modernist planning thought into five pillars include:

- Planning –meaning city and regional planning- is concerned with making public/political decision more rational.

- Planning is most effective when it is comprehensive.

- Planning is both a science and an art, based on experience, but the emphasis is usually placed on the science. … Planning knowledge and expertise are thus grounded in positive science, with its propensity for quantitative modeling and analysis

- Planning, as part of the modernization project, is a project of state-directed futures, with the state seen as possessing progressive, reformist tendencies, and as being separate from the economy.

- Planning operates in ‘the public interest’ and planners’ education privileges them in being able to identify what that interest is. (Sandercock, 1998: 27).

Postmodernism

Postmodernism arose out of the peculiar confusion in the social science. This confusion has two distinct components: a concerted general attack on the legitimacy of social sciences and a renaissance in the specific realm of social theory (Dear, 1987: 368). The meanings of postmodernism are ambiguous since the meanings of modernism are frequently ambiguous.

Harper and Stein (1995) identify key themes of postmodernism which they believe are relevant to the planning domain –antifoundationalism, meaning and ambiguity, incommensurability, dualism of truth and reason, and plurality and difference. They argue that postmodernism is antifoundationalist in dispensing with universals as bases for truth and in rejecting claims of undisputed authority. Postmodernists make much of the ambiguity that follows from their antifoundationalism. They take ambiguity to mean the inability to fix a universal meaning to a concept.

Harper and Stein (1995) identify the danger of incommensurability in postmodernism arises not from acknowledging that there are competing goals or different views of justice and morality, but from relativizing these differences to particular communities without the possibility of their coming together. They assert that postmodernism rejects dualism and propose that pluralism should replace dualism. They posit that the way to deal with differences in postmodernism is not by presupposing incommensurable notions of rationality and truth, but by talking about them and attempting to reach consensus.

Innes (1997) identifies the post modern era that is characterized by fragmented power, distrust of government and experts, incommensurable discourse, and a new tribalism where groups celebrate their differences. Planning education must be able to enrich the body of knowledge in particular that of making connections among interests, public agencies, and profession and disciplines, between public and private sector and between government and the public. Innes (1997) posits that the planning educators need to develop new intellectual frameworks more suited to the post modern era. If we could do so, Innes (1997) believes that planning is better able to adapt to change than many other fields. The 21th century can be the century for the field of planning if the planning educator and practicing planner make it so.

Postmodernists Critique of Modernist Planning Practice

Rationality

The important premise of modernist planning is rationality. Planning seeks to bring order through reliance on rational decision making and emphasis on quantitative analysis, neutral expertise and the provision of answers for decision makers (Innes, 1995; Sandercock, 1998). When the rational planning model was seen as foundational, planning educator was primarily a matter of technical training. The focus of planning education was on the empirical and the quantitative coursework.

One reason for the growing influence of the postmodern approach to planning is the demise of the rational planning model. The foundation of scientific rationality has been undermined but nothing has taken its place (Harper and Stein, 1996). In the last two decades, using the premises of postmodernism, there were found some shortcomings of rational planning model, as follows:

- Wicked problem; rational decision making is based on a faulty epistemology. Social problems are never solved, they are merely displaced by other problems.

- The veil of time; how to deal with the future. Forecasting is difficult.

- Pitfall in modeling, data analysis, optimization methods.

- Attention and information are limited, and interests constrain feasible alternatives.

- Goals are fuzzy, and criteria for evaluating consequences conflict with one another

- Rationality omits a significant portion of the relevant universe of action and interaction, not account for pre-interactive decision making or deliberation.

- Rationality has virtues as a guide for collecting and analyzing information, but in analyzing problems will see situations abstractly, narrowly, and superficially and will likely to fail to understand what social conditions mean to the people who live them.

Comprehensiveness

Comprehensiveness in a plan in which modernism claims as the way to interpret reality and exclusive insights into proper values and behavior was criticized by postmodernism. The claims of comprehensiveness, integrated and coordinated actions of multi-sectoral and multi-functional violate the complexity and contingency of social reality, and impose exclusionary perspective on individuals who are culturally diverse (Beauregard, 1991 ; Sandercock, 1998). For postmodernism, there are only multiple narratives, a multiplicity of language games that are locally determined, none of which can be reconciled across speakers and all of which must be allowed their existence (Beauregard, 1991: 193).

Sandercock (1998) argues that planning is no longer exclusively concerned with comprehensive, integrated, and coordinated action, but more negotiated, political, and focused planning. This in turn makes in less document-oriented and more people centered (Sandercock, 1998: 30).

Ways of knowing

Modernist planning hold that the authority of planners derives in large measure form a mastery of theory and knowledge in the social science. Thus, planning knowledge and expertise are grounded in positive science, with its propensity for quantitative modeling and analysis (Sandercock, 1998: 27).

Postmodernist perceives knowledge as inherently unstable that we only know the world through the argument about it. Thus, the knowledge is not necessarily a reliable guide to effective action. Increased understanding can only reveal differences, not set direction. To this extent, the important thing is not causality –cause and effect relations- but meaning.

Postmodernism is concerned with symbolic representations of action and behavior. Its task is to uncover the transmitted pattern of meaning by which men communicate, perpetuate and develop their knowledge about and attitudes toward life. (Beauregard, 1991). Language is a reflection of the attributes of a community. (Harper and Stein, 1996). Harper and Stein (1996) define community as “a social group whose members share common characteristics of heritage, beliefs, attitudes, hopes, history, culture, reflected in a common language” (p.418). Interpretation of what people do reflects their intentions, beliefs and hopes. Language cannot be separated from meaningful action.

Sandercock (1998) argues that local communities have experiental, grounded, contextual, intuitive knowledges, which are manifested through speech, songs, stories, and various visual forms rather than the more familiar kinds of planning sources such as census data, and simulation model. She suggests that planners have to learn to access these other ways of knowing

State directed vs. community-based

Modernist planning including rational planning, the incrementalist approach are classified as the social reform tradition (Friedmann, 1987). Planning is considered as a project of state directed futures. State is seen as reformist tendencies and as being separate from the economy. Planning in the social reform tradition acknowledges that there would be an inherent tendency to resist change that would give rise to conflict. However, modernist believes that these conflict situations are manageable and through rational decision making and that conflict creating situations can be eliminated or at least minimized and better managed. Modernist planning also believes that conflict can be avoided through appropriate intervention at the right time (Friedmann, 1987).

Postmodernist critique calls for community-based planning. It would replace modernist reliance on state-directed futures and top-down processes. From this perspective, citizens could dictate the agenda of the local government. Participation can lead to better public policy even if citizens bring their own narrow and selfish interest into politics. Through such selfish participation, the government is informed of these interests and pressured to respond. In this way, it produces public goods more closely attuned to citizen needs than it would if there were no participation (Verba, 1972). Verba identifies four modes of participation as alternative ways in which citizens can participate. They are voting and campaign activity which relate to electoral activity, and cooperative activity and citizen-initiated contacts which relate to non-electoral activity. The modes of participation are meaningfully different ways in which individual citizen tries to influence his government. They fit closely alternative systems of citizen-government interaction.

Public interest

The domain of planning in modernist paradigm operates in the public interest and planners seek to identify that interest within community. Planners attempt to present a public image of neutrality and planning policies based on positivist science. The notion of public interest comes from a frame of reference in liberal political theory in which disinterested experts objectively and rationally analyze a problem and arrive at a solution that is in the public interest. It assumed the ability of a certain chosen, well-educated group to stand outside social processes and decide what is best for everyone else (Sandercock, 1998: 197).

Sandercock (1998) argues that the construct of the public interest and community exclude difference. She suggests that we must acknowledge that there are multiple publics and that planning in this new multicultural arena requires a new kind of multicultural literacy (Sandercock, 1998: 30).

Urban Theories from the Developed World

Two urban theories, the Chicago School of Urban Sociology and the Los Angeles School of Urban Geography have dominated the discourse of urban development in developing countries, including in Indonesia. Both urban theories are based on phenomenon that occurred in urban cities in the United States. The Chicago School of Urban Sociology, which was developed in the early 1920s explain the development of the urban migration that is controlled by generating ecological patterns, such as invasion, survival, assimilated, adaptation and cooperation. The Los Angeles School of Urban Geography initiated in the late 1990s to explain the development of metropolitan Los Angeles in the postmodern era that emphasizes the importance of the capitalist economic and political globalization of the economy.

The dominance of both urban theories in the discourse of urban development influences the urban spatial planning in developing countries. Planning practices that replicate both urban theories through the dichotomy of developed and developing countries become ubiquitous. This becomes a problem when such a replication is no longer relevant with the unique urban phenomenon in developing countries, such as the informal sector.

Neither the Chicago School of Urban Sociology nor the Los Angeles School of Urban Geography can explain the unique urban phenomenon in developing countries, including the informal sector. Both urban theories are rooted from the developed world where the informal sectors or other unique urban phenomenon in developing countries are not commonly found. The local knowledge or local wisdom plays an important role in explaining the unique urban phenomenon in the developing worlds. The local knowledge or local wisdom can be an important factor in addressing any urban problems due to the unique urban phenomenon in the developing worlds.

The dominance of the Chicago and Los Angeles Schools in the practice of urban planning in Indonesia has contributed to the lack of spaces for the informal sectors in urban areas. The spaces in urban areas are dominated by the urban sectors that have high economic value and the spaces for the informal sectors are marginalized.

The application of local knowledge or local wisdom in understanding the phenomenon of street vendors will change our perspective on the existence of street vendors in urban areas. The street vendors are not the groups failed to enter the economic system in urban areas. They are one component of the urban economy that will benefit urban development. The application of local knowledge or local wisdom in the practice of urban planning will allocate more urban spaces for the street vendors and integrate it with the formal sectors.

Modifications to Urban Planning Practice

In light of postmodernist critique of the knowledge foundations of modernist planning practice and theory and the inappropriateness of the two urban theories rooted from the developed world in the developing countries, I would argue that some suggestion will likely enhance urban planning practice in the 21st century in the developing countries, particularly in Indonesia that characterized by fragmented power, distrust of government and experts, and incommensurable discourse, as follows:

- Planning needs greater and more explicit reliance on local wisdom rather than means-end rationality.

- Planning needs to move form top-down processes to community-based planning, geared to community empowerment.

- Planning needs to deconstruct the public interest and community and acknowledge there are multiple publics and thus planning requires a new kind of multicultural literacy.

- Planning needs to embrace plurality and difference. The post-modern critique calls for planner to abandon the belief that there is absolute truth or a unitary public interest.

References:

- Altchuler, Alan. (1965). The goals of comprehensive planning. The City Planning

Process: 299-332. - Beauregard, Robert A. (1989). Between modernity and

postmodernity: the ambiguous position of U.S. planning. In Readings in Planning

Theory. Scott Campbell and Susan S. Fainstein (Eds.). Malden: Blackwell

Publishing. - Beauregard, Robert A. (1991). Without a net: Modernist planning

and the postmodern abyss. Journal of Planning Education and Research 10(3):

189-194. - Blower, A. (1986). Town Planning: Paradoxes and Prospects. The

Planner. - Dalton, L.C. (2001). Weaving the fabric of planning as education.

Journal of Planning Education and Research 20(4): 423-436. - Dalton, Linda C. (1986). Why the rational paradigm persists: the resistance of professional

education and practice to alternative forms of planning. Journal of Planning

Education and Research 5: 147-153. - Dear, Michael J. (1986). Postmodernism and planning. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 4: 367-384.

- Friedmann, John. (1987). Planning in the Public Domain: From Knowledge to

Action. Princeton: Princeton University Press. - Harper, T.L., and Stein, S.M. (1995). Out of the postmodern abyss: Preserving the rationale for liberal planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research 14(4): 233-244.

- Harper, T.L., and Stein, S.M. (1996). Postmodernist planning theory: The

incommensurability premise. In Explorations in Planning Theory. Seymour J.

Mandelbaum, Luigi Mazza, and Robert W. Burchell (Eds.). Rutgers: Center for

Urban Policy Research. - Healey, Patsy. (1997). Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Society. UBC Press

- Innes, J. (1997). The planners’ century. Journal of Planning Education and Research 16(3): 227-228

- Roy, Ananya. (2005). Urban Informality: Toward an Epistemology of Planning.

Journal of the American Planning Association 71(2): 147-158 - Sandercock, Leonie. (1998). Towards Cosmopolis: Planning for Multicultural Cities. London: John Wiley and Sons.

- Verba, Sydney, and Norman Nie. 1972. Participation in America: Political Democracy and Social Equity. New York: Harper and Row

Six elevated toll roads should be revisited

The other four toll roads including Kampung Melayu-Kemayoran, Pasar Minggu-Casablanca, Kampung Melayu-Duri Pulo and Ulujami-Tanah Abang will be built in next three phases. The six elevated toll roads will add 67.74 kilometers to the Jakarta’s road length and will cost Rp. 40 million (US$ 4.4 billion). Are these new elevated toll roads going to reduce the traffic congestions in Jakarta? As many critics have said about these new toll roads, the new elevated toll roads will not alleviate the traffic congestions, but will even worsen the chronic transportation problems in Jakarta.

The traffic congestion in Jakarta can't be separated from the high growth rate of vehicle ownership -- 9 to 11 percent per year -- which is not supported by the growth of road development, which is only less than 1 percent per year. The development of new roads will never meet the high growth rate of vehicle ownership. A new highway or a widened road only alleviates traffic congestion for a short period of time. After a few years, any new highway fills with traffic that would not have existed if the highway had not been built. Similarly, any widened road fills with more traffic in just a few months. Such a phenomenon is called induced demand. Because of induced demand, neither building new roads nor widening roads are viable long-term solutions to traffic congestion.

The new toll roads will also undermine the efforts of developing the mass transportation system in Jakarta. The main idea of developing the mass transportation system including busway, monorail, and the Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) projects in reducing the traffic congestion is to reduce the number of car riders and motorcyclists in the Jakarta’s streets. The car riders and motorcyclists are expected to use the mass transportation modes and reduce the burden of the Jakarta’s streets. The new toll road will attract car riders back to the Jakarta’s streets.

Not only will the elevated toll roads cause the induced demand and worsen traffic congestion, but also could jeopardize the livability of neighborhoods along the elevated the toll road. In many cities in other countries, such as Seoul, New Orleans, San Francisco and New York City, the elevated freeways caused the declining livability of neighborhoods along the elevated freeways. In many developed countries, we have seen the shift in urban planning from enhancing mobility toward promoting livability.

The Chonggyecheon freeway was completed in 1977 and was also used as a symbol of modernization and industrialization in South Korea after the Korean War. This elevated freeway was built above 5.8 kilometers creek flowing west to east through downtown Seoul. In 2000, the area was considered as the most crowded and noisy parts in the city of Seoul and became an eyesore of the city of Seoul. In July 2003, then-Seoul mayor, incumbent South Korean President Lee Myung-Bak, launched a project to destroy the Chonggyecheon freeway, revitalize the surrounding area and restore the river flow. During the demolition process of the Chonggyecheon freeway, the Seoul city administration also developed public transportation systems, including Bus Rapid Transit lines. Today, the Chonggyecheon area has been revitalized and become one of the main tourist attraction areas in the city of Seoul.

In 1973, New York City’s West Side elevated highway collapsed and was never repaired but replaced by a surface boulevard of West Avenue. Similarly, two elevated freeways in San Francisco, Embarcadero and Central Freeways, were badly damaged by the Loma Prieta earthquake of 1989. The San Francisco city administration decided not to rebuild the elevated freeways, but replaced them with surface boulevards. The conversion of elevated freeways in both New York City and San Francisco did not cause traffic havocs. The traffic switched to the boulevards, nearby street or mass transit (James and Norquist 2010). Furthermore, a team of researchers from the UC Berkeley (Cervero, Kang, and Shively 2009) found that the conversion of elevated Embarcadero and Central Freeways with boulevard has stimulated reinvestment in the neighborhoods along the freeways without seriously sacrificing transportation performance. More recently, the residents of New Orleans have decided not to rebuild the damaged elevated expressway caused by the Hurricane Katrina, but replace it with an oak-lined boulevard (James and Norquist 2010).

The conversion of elevated freeways to surface boulevards in Seoul, New York City, San Francisco or New Orleans is evidence of a paradigm shift from a focus on expediting the movement of automobile to a focus on increasing the livability of neighborhoods. The livability of neighborhoods should be prioritized over the increase of mobility. Jakarta needs to learn from what has happened in Seoul, New Orleans, San Francisco or New York City regarding the elevated freeways. Not only is the proposed six elevated toll road projects the solution for the traffic congestion in Jakarta, but also they could cause the decline of livability of neighborhoods along the elevated toll roads. The Jakarta city administration should revisit their decision to build the new elevated toll roads and instead they should focus their efforts on building mass transportation systems in alleviating transportation problems in Jakarta.

References:

- Cervero, R., Kang, J., and Shively, K. (2009). From elevated freeways to surface boulevards: neighborhood and housing price impacts in San Francisco. Journal of Urbanism 2(1): 31-50

- James, C. and Norquist, J. (2010). Tearing down an expressway to restore a community. http://www.nola.com/opinions/index.ssf/2010/08/tearing_down_an_expressway_to.html

(This article also appeared at The Jakarta Post on September 4, 2010)

Jakarta needs Metro to avoid traffic gridlock